EU policies, including enlargement, received scant attention in the run-up to the October 29 elections in the Netherlands. Yet, the next Dutch government might be a key factor in Montenegro’s and Albania’s bids to join the EU. Difficult coalition talks will determine whether the Dutch position will be critical but constructive, or outright sceptical. Based on preliminary election results, this blog takes a look at possible coalitions and their stances, as well as at public perceptions and attitudes.

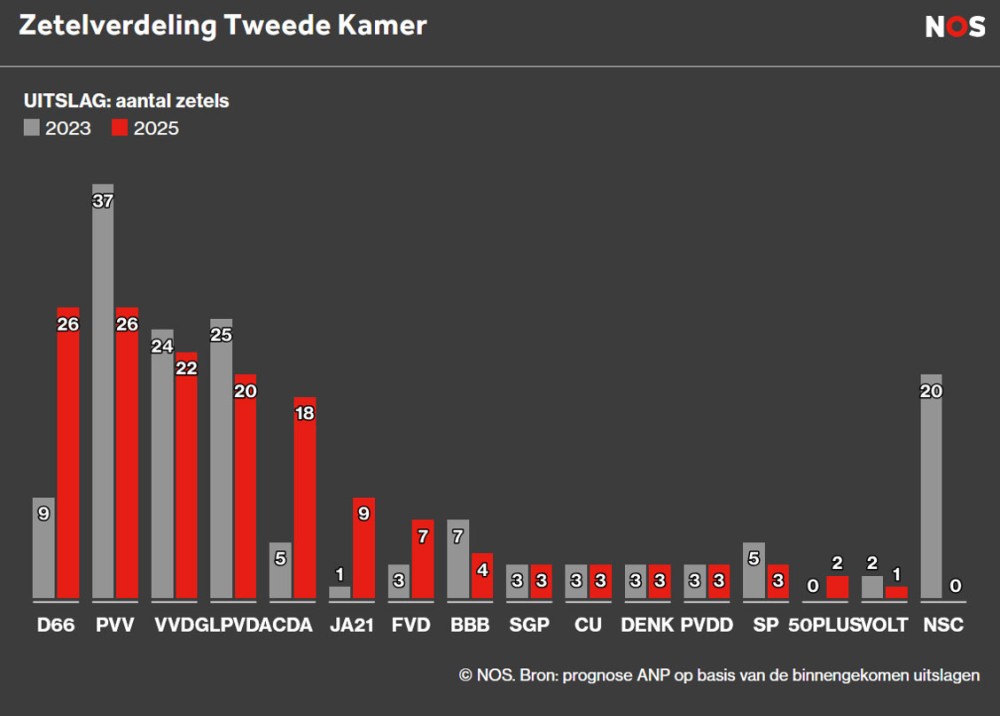

With a relatively high voter turnout of over 78 percent, the Dutch electorate set the course for what is bound to be another round of difficult coalition talks in The Hague – a process that could take months. As there is no electoral threshold, up to 15 parties are expected to be represented in the next parliament. In a surprising twist, the social-liberal D66 matched Geert Wilder’s notorious right-wing populist Freedom Party (PVV), both likely gaining 26 seats, with the final winner only to become clear when all votes have been counted. Three other parties followed suit with 18 to 22 seats each. These parties, as well as D66, have excluded collaborating with Wilders’ party after their exit from the last government. The most likely scenario now is either a centre-left government where D66, CDA (Christian Democrats) and VVD (Conservative Liberals) join forces with the GL-PvdA (Social-Democrats/ Greens), or a centre-right government comprising, in addition to D66, CDA and VVD, the more radical right JA21, the farmers party BBB, and/or smaller Christian parties. Given the election outcome, negotiations for any coalition could take several months. What could these preliminary election outcomes tell us about the future Dutch stance towards EU-enlargement?

Preliminary election results as of 30 October. Source: NOS.nl

From enlargement sceptics to cautious supporters?

The Netherlands, together with France, is among the most enlargement-critical member states. Alongside Paris and Copenhagen, it voted against the opening of accession negotiations with Albania in 2019. For several years, The Hague blocked Kosovo’s visa-liberalisation at odds with the recommendations by the European Commission, citing concerns on rule of law compliance in both cases. While not rejecting EU enlargement as such, Dutch strictness towards EU candidates can at least partially be attributed to political EU scepticism in part of its political scene.

While officially aligning with the EU designation of enlargement as a “geo-strategic investment in peace, security, stability and prosperity”, Dutch politicians have been chief among those pointing out the importance of strict rule of law conditionality and a merit-based approach, consequently placing the interest of a solidly functioning European Union above geopolitical imperatives for further enlargement. Any potential doubts in the government or parliament about the readiness of Montenegro and Albania to join the EU could lead to a Dutch veto, thereby obstructing the process now driven forward by the Commission and these candidates.

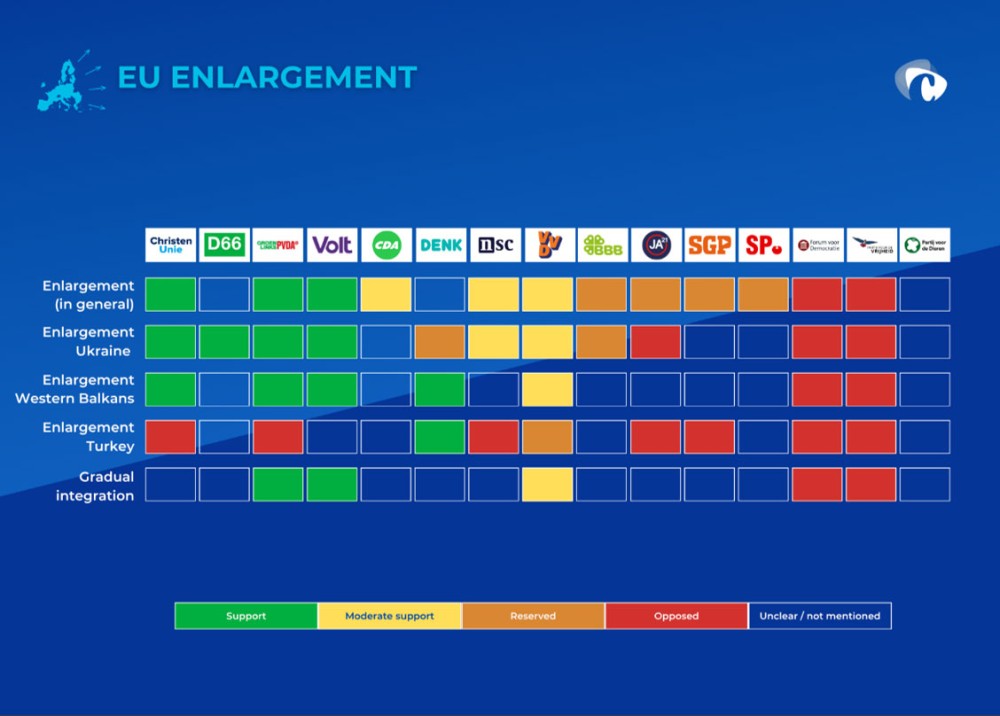

At the same time, the election programmes of the political parties (see figure below) and a recent large-scale public survey paint a somewhat more pro-enlargement picture. While EU-sceptic PVV rejects enlargement on principle, the other four of the top five political groups support it either outright or at least conditionally. D66 is explicitly in favour of swift enlargement, especially for Ukraine, while the coalition between the Labour Party (PvdA) and the Greens (GroenLinks) pleads for active support for the candidate countries, with the exception of Turkey, and supports gradual integration. The Christian Democratic CDA and conservative-liberal VVD both emphasise strict adherence to the Copenhagen Criteria in their party programmes, but also note the need for enhanced cooperation with candidate countries while maintaining a credible accession perspective.

A coalition of these four, suggested as a “logical option” by D66 leader Jetten during election night, could therefore pave the way for a more pro-active Dutch role in Brussels, and more support for enlargement in tandem with necessary reforms on all sides to safeguard the rule of law in a Union of potentially more than 30 member states. Should D66 accept a more centre-right coalition with CDA, VVD, and for instance, radical-right JA21 and BBB, the next government would be bound to be more reserved both towards enlargement and EU policies more broadly. Either way, the coalition talks promise to be tough, not least as VVD leader Dilan Yeşilgöz has priorly rejected a coalition with GL-PvdA. It is unclear whether she will stick to that position now former EU Commissioner Frans Timmermans renounced his leadership of the party after the exit polls were published.

Support for EU enlargement among Dutch parties. Source: Sam de Vet, Wouter Zweers, Saskia Hollander / Clingendael

Growing support, little debate

When it comes to public opinion, the latest Eurobarometer data which included 1021 Dutch respondents came as a surprise for many observers: The Netherlands Ranks among the top ten supporters of EU enlargement, with more than half of those interviewed favouring the accession of all Western Balkan and Eastern candidate countries but considerably less support for Turkey (39 percent). Interestingly, in spite of the 2016 referendum rejecting Ukraine’s Association Agreement, in the new geopolitical context Dutch citizens seem to recognise the geopolitical imperative of Ukraine’s EU bid, with 65% supporting it. Equally surprising, fears of excessive migration from new member states are much less pronounced than among other EU member states and dwarfed by concerns over the functioning of a Union of more than 30 countries, mirroring the demand for comprehensive reforms not only in the accession states but also within the EU governance system.

As is evident from both the party programmes and the survey, neither EU enlargement nor reforms are a central issue for either politicians or their voters, with the possible exception of Ukraine. Few parties make any concrete proposals, and the issue hardly plays a role in most manifestos. Similarly, two thirds of the Dutch Eurobarometer respondents do not feel (well) informed about the subject and the implications of a growing EU for its fundamental values and stability, reflecting a media landscape from which the topic has long been absent. This gap risks being filled with an increase in misinformation as the next enlargement round approaches, especially from Russia in combination with Dutch domestic anti-EU parties and interest groups who might try to hijack the debate, as was the case during the Dutch referendum on Ukraine’s Association Agreement. Hence, there is a clear imperative for any future centrist coalition to take EU enlargement seriously and raise the issue in political and societal debates.

All eyes on The Hague

Whatever coalition may come to the fore in the difficult talks expected to take months, it is evident that the Netherlands will maintain a relatively critical stance towards EU enlargement. The outcomes of such talks will determine the level of Dutch constructive engagement on the issue. For Albania and Montenegro, it is not only in their own interest, but also of utmost strategic importance to present a clear case for their accession to the member states. While EU enlargement rarely appears as a priority amongst Dutch political debates, a centrist coalition government is unlikely to block accession if it finds itself isolated in the European Council. After all, the Netherlands is not keen on further losing influence in the EU – a trend triggered by former PM Mark Rutte leaving the Dutch political scene. D66 leader Rob Jetten even called for a “return of the Netherlands to the role of kingmaker in Europe”. How this will play out will depend a lot on the next government – which, as things stand, he could well be the head of.